Martial law and the Philippine economy

Emmanuel S. de Dios, Maria Socorro Gochoco-Bautista, Jan Carlo Punongbayan

Clearly, therefore, the best performance in the Marcos era occurred in 1972 to 1980. This precedes the decline from 1981, which then ended with the crash of 1984 to 1985— the Philippines’ worst economic recession since World War II.

The crucial question for students of the period and citizens alike is whether the economic

crisis under the dictatorship was due to unfortunate circumstances, misguided policy, or

deliberate malfeasance and corruption—was it bad luck, bad policy, or bad faith? The short

answer is not one but all of the above.

Abstract

Part of a proposed anthology, this article provides a concise review of the economic performance during the period of the Marcos dictatorship (1972-1985) from a comparative historical perspective. We examine the external events and internal policy responses that made possible the high growth in the early years of martial law and show that these are integral to explaining the decline and ultimate collapse of the economy in 1984-1985. The macroeconomic, trade, and debt policies pursued by the Marcos regime—particularly its failure to shift the country onto a sustainable growth path—are explained in the context of the regime’s larger political-economic programme of holding on to power and seeking rents.

Golden Age or Poverty?

One of the first indicators that may point to the economic impact of the Marcos era is the change in poverty levels after his administration.

During the Marcos years we also lost our standing as one of the economic leaders in Asia. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, barring small nations like Brunei and Singapore, we had in fact the largest per-person income among ASEAN countries.

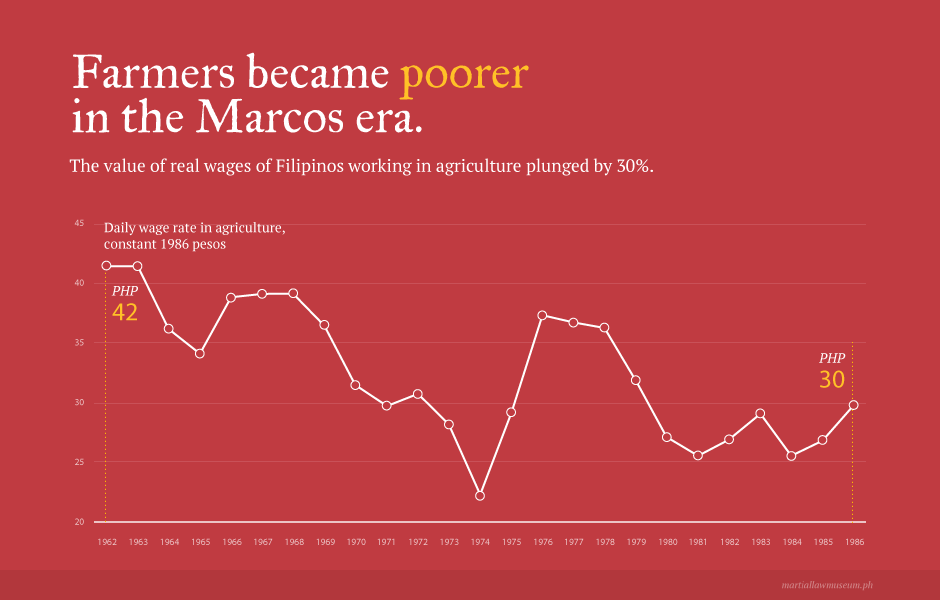

The daily wages of Filipino agricultural workers declined by about 30%, such that if a farmer earned Php 42 per day in 1972, he would only be earning about Php 30 in 1986. The wages of farmers even went as low as nearly half of the pre-Marcos values in 1974, right after the declaration of Martial Law.

Martial Law in Numbers

This file contains 150 economic indicators (and growing) with more than 3,500 data points from 1962-1986.

All in all, the Philippine economy suffered its worst during the Marcos regime. Marcos brought the economy to its knees, pulled down our country’s trajectory, and effectively “stole” our future incomes.

-martiallawmuseum.ph

- CEM E-books

- CEM Publications

- Collection highlights

- Course Resources

- Datasets

- Open Access Databases

- Open Educational Resources

- Databases

- CEM Special Collections

ACCESS VIA OPENATHENS

False Nostalgia: The Marcos “Golden Age” Myths and How to Debunk Them

Author: Jan Carlo B. Punongbayan, PhD, assistant professor, UP Diliman School of Economics (SE)

Category: Business and Economics

“This book is going to be perhaps the most lethal weapon in the arsenal against the so-far partially successful attempts (thanks to social media) to tout the 20-year Marcos era (January 1966 to February 1986) as a “golden age” in Philippine history. Specifically, JC Punongbayan relentlessly examines every one of 43 claims that have been made regarding that period—from the faintly ridiculous (that Imelda Marcos did not use public funds to build her “bopis” hospitals) to the utterly insane (that nobody was poor during the Marcos regime). He debunks every one of them with a mountain of data and past studies, all footnoted, referenced, and acknowledged so anyone can check and see for themselves the accuracy of JC’s rebuttals. The joy is that he combines seven years of scholarly research with simple, clear, compelling writing. Bravo!” — Solita C. Monsod , Professor Emeritus, UP School of Economics

Passionate Revolutions : The Media and the Rise and Fall of the Marcos Regime

Author: Talitha Espiritu

In the last three decades, the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos has commanded the close scrutiny of scholars. These studies have focused on the political repression, human rights abuses, debt-driven growth model, and crony capitalism that defined Marcos‘ so-called Democratic Revolution in the Philippines. But the relationship between the media and the regime’s public culture remains underexplored. In Passionate Revolutions, Talitha Espiritu evaluates the role of political emotions in the rise and fall of the Marcos government.

Focusing on the sentimental narratives and melodramatic cultural politics of the press and the cinema from 1965 to 1986, she examines how aesthetics and messaging based on heightened feeling helped secure the dictator’s control while also galvanizing the popular struggles that culminated in “people power” and government overthrow in 1986. In analyzing news articles, feature films, cultural policy documents, and propaganda films as national allegories imbued with revolutionary power, Espiritu expands the critical discussion of dictatorships in general and Marcos‘s in particular by placing Filipino popular media and the regime’s public culture in dialogue. Espiritu’s interdisciplinary approach in this illuminating case study of how melodrama and sentimentality shape political action breaks new ground in media studies, affect studies, and Southeast Asian studies.

Reading List

Reyes, P. L. (2018). Claiming History: Memoirs of the Struggle against Ferdinand Marcos’s Martial Law Regime in the Philippines. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 33(2), 457–498. https://doi.org/10.1355/sj33-2q

Tadem, E. C. (2015). Technocracy and the Peasantry: Martial Law Development Paradigms and Philippine Agrarian Reform. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 45(3), 394–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2014.983538

Yu, N. G. (2006). Interrogating social work: Philippine social work and human rights under martial law. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00401.x

Mananzan, M. J. (2002). Church-State Relationships During Martial Law in the Philippines 1972-1986. Studies in World Christianity, 8(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.3366/swc.2002.8.2.195

Encarnacion Tadem, T. S. (2013). Philippine Technocracy and the Politics of Economic Decision Making During the Martial Law Period (1972-1986). Social Science Diliman, 9(2), 1–25.

Snyder, K. A., & Nowak, T. C. (1982). Philippine Labor Before Martial Law: Threat or Nonthreat? Studies in Comparative International Development, 17(3/4), 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02717302

Ben Kerkvliet (1973) Agrarian conditions in Luzon prior to martial law, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 5:2, 36-40, DOI: 10.1080/14672715.1973.10406333

Crowther, W. (1986). Philippine Authoritarianism and the International Economy. Comparative Politics, 18(3), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/421615

Reyes, P. L. (2018). Claiming History: Memoirs of the Struggle against Ferdinand Marcos’s Martial Law Regime in the Philippines. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 33(2), 457–498. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26538540

First Floor, REDREC Building, UP Los Baños, College Laguna

cemlibrary.uplb@up.edu.ph

SERVICE HOURS

MONDAY- FRIDAY

7:30 AM to 5:00 PM

Closed on weekends

Closed during regular Ph holidays and declared work suspensions.